Electronic Enlightenment colloquium on the sociology of the letter

The Correspondence of Esther Masham and John Locke: a study in epistolary silences — Susan Whyman

In 1722, Esther Masham, a forty-seven-year-old Essex spinster, was copying letters into a book. On the first page she inscribed the title, “Letters from Relations & Friends to E Masham, 1722 Book 1st.” Her preface on the next page explained her intentions:

The reason why the following Letters are collected in this manner, is done purely for my own diversion and amusem’t and not with any view that they may become the entertainment of others. I do it to rid my self of heaps of papers y’t would . . . be useless to others after me & to prevent their becomeing Pye papers, serving to set up candles, or at best being made thread papers. Such Letters—as I think by being kept may do prejudice either to ye writers or my self I commit to the flames. By doeing this I preserve to my self . . . the Pleasure of reading again the Letters of Relations & friends gone before me as well as of Liveing absent ones. It makes me reflect on passages of my past Life & it serves [to] divert some Melancholy houres of a Solitary Life. These Reasons I hope are sufficient to satisfie ye Curiositie of any into whose hands chance may hereafter bring these Papers tho’ not designed for Publick view but only for my private satisfaction.1

Readers familiar with women who copied and preserved their family histories will find few surprises in Esther’s aversion to publicity or in her references to a private life marked off clearly from the public world. At first glance, the letter book seems to tell an unadorned tale of the lives of an Anglo-French Huguenot family through 143 letters (45 of them in French) written between July 1686 and August 1708. The largest number of correspondents are aunts, cousins, and friends, but there are also 12 lively letters from the philosopher John Locke (1632–1704), replete with intimate nicknames and private jokes.2 Locke spent the last thirteen years of his life with the Masham family at Oates in Essex, and the book probably escaped destruction because of his letters.

In 1876, a Locke biographer published a few extracts from what he claimed were two volumes of Esther’s letters.3 After years of neglect the letter book was sold in 1939 to the Newberry Library, where it was tracked down by Maurice Cranston. Cranston transcribed Locke’s letters for publication in the Newberry Library Bulletin,4 and they were included by E. S. De Beer in his eight-volume edition of Locke’s correspondence.5 Esther’s letter book contains only copies of incoming correspondence, but two original letters from Esther to Locke are found in the Bodleian’s Lovelace Papers.6 They show her everyday writing in a free-flowing hand, which contrasts with her careful copying of the letters that she received. Esther’s letter book is important not just as a material record but also as a lens to illuminate wider issues: changing attitudes toward authorship in terms of gender and class; the construction of personal identity; and the definition of private and public space at a time when print technology was challenging handwritten communication. Yet the letter book has been neglected, and the life of its compiler remains unknown.7

Esther’s preface, despite its apparent clarity, is not entirely convincing. Why, for example, did she feel the need to provide seven different reasons for creating her book? Her defensive apology and virtuous list of motives of course exemplify a convention found in the prefaces to works by other women writers. Yet Esther’s final sentence confesses that her intentions may be defeated and that commendable “private satisfaction” may give way to the abhorred “Publick view.” These are signs of a rhetorical strategy that conformed to accepted gender norms but was in fact underpinned by doubts. This ambivalence indicates that Esther was living at a time when attitudes toward public authorship were undergoing change. Women were revising their own ambitions and society was altering what it would allow.

Since classical times, a myth had gradually arisen that letter writing was a distinctly feminine genre, in which women excelled.8 But a corollary to this belief was that virtuous women did not publish their writings. Concepts of feminine modesty, morality, and reputation traditionally precluded any thought of publication. Silence and obedience were natural attributes of a virtuous life. Learned ladies, on the other hand, were bemusedly mocked. “Whatever learning a girl acquired,” cautioned Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, “should be concealed as though it were a physical blemish lest it arouse envy and hatred.”9 Conduct books helped women accept gendered roles, and class norms operated in a similar fashion to protect gentility.10 Elite women like Lady Mary knew that “it would have been too déclassé to print.”11 On the surface, women’s lives were hedged with restrictions buttressed by education, religion, and the law.

Of course, women had long found solace in writing what Margaret Ezell calls “closet texts,” and feminist scholarship has reclaimed a wealth of women writers. Yet if traditional norms were working reliably, their audiences would have most likely been limited to “God and the author.”12 In this conservative framework, contemporary definitions of the terms “public” and “private” were perceived as stable and clear. Esther’s doubts about the privacy of letters, however, signal that a broad spectrum of attitudes toward authors and readers had developed over time. This range of possibilities challenged the long-standing dichotomy of public and private spaces and invited women to employ various strategies to enter the world of letters.

As we place Esther’s letter book in its historical framework, we note that it was created at a time when print technology was challenging handwritten communication. At the same time, letter writing was assuming new importance. Since letters were central to all the basic forms of printed discourse—newspaper, proclamation, broadside, journal, and the novel—epistolary analysis can offer new ways of looking at eighteenth-century culture generally. I have argued elsewhere that a convergence of factors led to a flourishing “culture of letters” in the long eighteenth century (1660–1800).13 Increased wealth and levels of literacy were creating a vast national supply of letter writers and readers.14 It is not surprising that the first novels were epistolary, nor that they found a growing readership after the Restoration. The demand for postal service and the development of the post office after the Civil War meant that reliable communication across considerable distances was possible for the first time.15 In the face of expanding war, empire, and trade, and the breakup of village life, people were experiencing new patterns of mobility and separation. More social as well as mercantile transactions were occurring with those who were physically absent, which led to changing views about space, time, and distance. Letter writing now became a part of everyday life.16 By the end of the seventeenth century, ordinary people were increasingly just “scribbling” their thoughts to family, friends, and lovers in intimate personal letters. This newfound ability to communicate across space gave writers a sense of power. The result was a cultural shift in the structure of communications and the social relationships that they produced.

Although Esther did not admit it, I believe that she was using her letter book to negotiate her own entrance into the world of letters. I now ask the reader to look between the lines of Esther’s preface and to find unexpressed motives for creating her book. I suggest that in the act of copying letters, Esther was re-addressing them to a new audience that was larger than she admitted. Although letters have often been viewed as simple, transparent texts, Esther’s book forces us to reconsider whether they are indeed “windows into the soul” or highly crafted pieces of artifice and convention. By asking what Esther included, what she left out, and why, I will show that her letter book was carefully constructed to tell a specific story about her family and their relationships with Locke. Social conventions hindered her from speaking out herself, but she could tell her story by copying other people’s letters. Esther had a practical and personal agenda, and her epistolary silences are perhaps more important to its accomplishment than the intentions stated in her preface. When Esther and her family are placed in their historical framework, these silences become laden with meaning. They invite us to probe into Esther’s social and cultural context, her family background, and the larger world of letters of which she was a part.

When the letter book is combined with other types of documents, it provides evidence of this context. It also raises questions about the use of letters in historical research. Clearly, letter collections as a genre lend themselves to a combination of narrative and statistical analysis. The letter book enables the creation of a database with information about writers, recipients, and contents, as well as epistolary manners, such as forms of address and “humble services.” We can also construct two family trees showing Esther’s French and English families. But in order to fill in the silences, we must supplement the letters with wills, memoirs, genealogies, county and city histories, literary works, pamphlets, and periodicals.17 In the first part of this essay, I use this context to reveal Esther’s story of herself and her family, and of her close acquaintance with Locke. In the second part, I assess her role as an author at this pivotal moment in the history of manuscript culture.

In 1691, Locke moved to Oates, the Masham family’s Tudor manor house in Essex, twenty-five miles from London. Drawings locate the two rooms in which he worked, next to a turreted tower.18 The household, staffed by ten servants, included Esther’s father, Sir Francis (1646–1723); her stepmother Damaris Cudworth Masham (1659–1708), age thirty-two; Damaris’s young son, Francis (1686–1731), age five; Esther’s eight brothers (when they were on leave from service in the wars against France); and Esther (1675–1728), age sixteen. In 1685, Damaris described her as “a Girl . . . that speakes not yet a Word of English.” In 1697, Pierre Coste, a French Huguenot who became tutor to Francis, joined the family.19

Before Locke moved to Oates, he had been living in London lodgings after years of Continental exile. Denied his old place at Oxford, he was suffering from asthma in the city. The Mashams’ invitation suited him for many reasons. One of them related directly to Esther and her brothers. “For a man who based theories of knowledge on domestic experience,” notes Sheryl O’Donnell, “what better place to live than in a bilingual household with young children.”20 Locke insisted on paying for his lodging, a pound a week for himself and his servant, plus one shilling for his horse.21 For thirteen years, the family crowded together, accommodating themselves to Locke’s many visitors and possessions. The latter included his writing desk, a specially constructed chair, a telescope, botanical specimens, a great porous stone through which all the water he drank was filtered, and his four thousand books—“big books, great sets of leather folios weighing a stone or more a set.”22 In 1692 at Christmas, the house was so crowded that Esther had to lie “in a servants chamber and bed in the passage to the Nursery.”23 Under these living conditions, Esther and the great philosopher developed a close and affectionate relationship.

The Masham family were originally from Yorkshire, but William Masham, a London merchant, increased the family fortunes, and by 1621 his descendants had bought both Oates and a baronetcy.24 By 1690, Esther’s father represented Essex in Parliament.25 Despite his court connections, he never found a husband for Esther. His deceased first wife, Mary, Esther’s mother, was the daughter of Sir William Scott, baronet and marquis de la Mezangère. Sir William had befriended the future Charles II in exile and become a naturalized Frenchman with property at Rouen.26 We do not know where Esther spent her early childhood, but it was somewhere in France. In annotations to the album’s first letter, from her aunt, Scott Le Gendre, she notes that when she was eleven, in 1686, “I had been come out of France about a yeare or more.”27 There is no mention that the revocation of the Edict of Nantes had taken effect on 8 October 1685 or any indication that her journey to England was a flight from religious persecution. This is the first instance of her epistolary silences, but the letters reveal how religious faith, anti-French sentiment, and war affected Protestants on both sides of the Channel.28

As Esther’s own annotations and marginalia show (for some examples of these, see illustrations, pp. 16–19 [I cannot check this. Are you publishing the illustrations?]), her aunts and uncles, who had married in France, formed three large interconnected families.29 The de Drumares and Le Gendres in Rouen were proud of their offices and wealth. But because Esther’s aunts and female cousins remained staunch Protestants, they lived in fear of reprisals. Two of Aunt Le Gendre’s daughters in France were forced to go to Mass. Her two sons were in England in the 1680s, and they fled to Holland before returning to France.30 Esther’s French kin wrote of friends in hiding, confiscation, forced church attendance, and painful separations. One cousin, Catherine de Drumare, had decided to settle in London rather than change her faith. When her mother died, she was the only child who was not at the funeral.31 As Esther copied the letters, she was constructing a family portrait that expressed her family’s pain and suggested their courage in adversity.

Esther received loving letters from her eight brothers. Two of them had been educated in Caen but all of them now lived in England. Totally bilingual, they slipped into French in mid-sentence if they were discussing delicate matters.32 One brother died in St. Helena as a chaplain to the East India Company.33 The others served in the English army against France and struggled to find good posts. Their letters aboard ship or from camps in Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Gibraltar, and Flanders capture the plight of younger sons, the immense importance of letters, their fears before and after battle, and the social impact of the French Wars. They offer scholars a wealth of material on the subject of masculinity. We see young soldiers fighting their own former countrymen and trying to fit into accepted gender roles that stressed bravery and manliness. Underneath the bravado, however, they reveal sensitivity and fear. They speak movingly in gendered voices about isolation, war—and letter writing.34

Despite enforced silences during wartime, Esther wrote regularly to her French kin. She also sent them news, gifts, and books, especially those written by Locke. Aunt Le Gendre enjoyed reading that “beau livre,” the Essay on Human Understanding.35 Her comment shows us that women were members of the republic of letters and that circulation of texts was wide and deep. In return, French kin sent Esther “keys” explaining characters in Madeleine de Scudery’s books, for they knew Madame deScudery and other writers.36 They respected Esther’s place in the world of belles lettres and acknowledged her intimacy with Locke. Her own letters, they suggested, were a most important link between the French and English families.37 Since Esther’s preface tells us that she pre-selected the letters that she copied, it is not surprising that they were extremely flattering to her.

Esther’s letters from French kin were not merely complimentary but were also marked by different notions of politeness. Because she often placed French and English letters side by side, we can easily see cultural differences in letter-writing practices.38 For example, the French used more complex forms of address and more lines of farewell. They left large spaces between salutations, text, and signature, designed to express deference, which Esther replicated. Compliments were integrated throughout the text; indeed, some letters contained nothing else. The French used far more lines to append humble services to fewer people.39 In contrast, English writers tacked on compliments at the end. English “humble services” appear to be leftovers from Continental usage that were originally used to show status, networks, and manners. Even Esther’s sister-in-law Abigail Masham promised never to use “formal insincerity,” as was common where she lived, at Court.40 English writers employed the terms “love,” “duty,” and “service,” in contrast to French compliments. Thus Esther’s brother Charles asked her to send his “duty” to his parents, and his “kind love and service” to all others, “when it is either due or may be expected.”41 A polite English person knew how and when to use compliments, which were an instant sign of breeding. The more intimate the writer, the less polite one had to be, but no single rule was sufficient. It was the subtle adjustments that counted.

Locke’s own correspondence mentions two of Esther’s brothers: Charles and also Henry, who had met the philosopher in Holland, volunteered in Flanders, and returned with William III to England.42 In 1698, during a short period of peace, Henry slipped into France to collect legacies due to Esther and her brothers. He was entertained regally by kin and a friend, Monsieur Gale (Galle). Gale was banned by court order from the Le Gendre house, for it was assumed that he was responsible for the aunt’s “being still a good Protestant, as well as her daughters.”43 At Paris, Henry searched at least twenty stores for a book Locke needed— Theopraste, with a key. Locke consulted it for several published works and it was listed in his library.44 Henry stayed in his cousins’ tents at their army camp and observed Louis XIV and the deposed King James of England review the troops. Henry’s hurried departure was occasioned by his fear of being taken as a spy.45 He found trunks that had been left in France by Esther, full of rotting linen, presumably intended for her dowry, and sold them all for a pittance.46 It is in the context of Esther’s fear for her brothers, the threat of war against kin, the uncertainty of her legacy and her lack of dowry, that we must read and interpret her letters.

Among the brothers only the youngest of them, Samuel, attained status and wealth in England and outlived their father. Profiting from Sir Francis’s court connections, he secretly married Abigail Hill, Queen Anne’s favorite, and became first baron Masham.47 The brothers’ loving letters, however, give the impression that Esther, not Sir Francis, was the center of the family. Letters from young English cousins begging Esther to join their ladies’ club show that she had networks of female friendship in London as well.48

The jewels in Esther’s epistolary crown are Locke’s twelve letters, starting in 1694, when she was nineteen. When we add her two surviving replies, found in Locke’s papers, we see an affectionate relationship between an elderly bachelor and an intelligent young woman.49 The letters Esther included were written mainly during summer, when dry weather enabled Locke to be away in London. The forms of address were often imaginative or showed intimacy: She called him her John. He used nicknames and diminutives derived from French and Spanish romances, including his favorite, Dib or Dab from Landabridis—meaning a lady love or mistress.50 Once he was “of all the Shepherds of [the] Forest . . . Yr Most humble & Most Faithfull Servant, Celadon the Solitary” (from Astraea ),51 but most often he was simply “Your Johannes.”52 The letters show deep affection but also reveal a tutor/student relationship that confirms Locke’s interest in child rearing and education. Locke used wit and raillery, but never harshly, and showed tenderness and love. His metaphors were just what he thought a young person would like, with references to sweet foods—cream and strawberries, cherries and brandy. The subjects range from the weather to music and romances, but books above all. Together the pair dug in the garden, observed nature, attended church, laughed at the minister’s foibles, sang songs, told jokes, and devoured books, especially the Bible.53 We see him buying Esther books of increasing difficulty, teaching her to love the Bible: in short, molding her behavior in accordance with his Some Thoughts on Education. He presented a copy to her in 1695.54 As in other gentry families, girls often became informal students of tutors who had been hired for boys. In this case, Esther would have had guidance from both Locke and Francis’s tutor, Pierre Coste.

Esther’s letters to Locke also dwell on her pretended and conventional jealousy of other women: a widow and a visiting duchess. Surprisingly, her stepmother, Damaris, is never mentioned. In fact, Esther’s letter book contains no letter from her father, Damaris, or their son Francis, though she was often separated from them. If it were not for the humble services mentioning Damaris in letters from French kin, one would never know from Esther’s selection that a stepmother had been installed at Oates in 1685.55

Because of this epistolary silence, we must supplement Esther’s own letters with other documents to find information about Damaris, Sir Francis, and their relationships with Locke. We know from Locke’s own letters that he and Damaris met in London when he was advising the earl of Shaftesbury. At that time, she was twenty-two and he was forty-nine.56 In fact, before he took up residence at Oates, they had been in constant correspondence for ten years. From 1682 to 1688, she wrote Locke (“Philander”) over forty intimate letters signed “Philoclea.” They contain an intense mix of philosophy and theology, rationality and emotion and, as W. von Leyden commented, are “uncommonly like love poetry.” Damaris and Locke discussed novel philosophical views that he had not yet published.57

Damaris has been described by turns as “fair and intolerably Witty,” moody, melancholy, and provocative, and the “first bluestocking.”58 Brought up in the all-male world of a Cambridge College, where her father, Ralph Cudworth, was master, Damaris became a publicly known learned lady. In a world that scoffed at such women, Locke prized her. His views about her remarkable mind are often quoted. While Locke was at Oates, she wrote two philosophical essays in a debate with Mary Astell against Platonism, publicly disowning her father’s views, though she had earlier defended them. She called for women’s education, along with Astell. But her belief that experience and reflection rather than innate ideas formed the origin of human knowledge linked her publicly with Locke.59 Recent studies view her as a serious, under appreciated philosopher and theologian in her own right.60

There has been much speculation about Locke’s relationship with Damaris. An opponent maliciously called him “the governor of the seraglio at Oates.” What scholars do agree upon is that she was “closer to Locke than any other human being.”61 Locke’s letters and accounts show how intricately their lives were enmeshed. He managed her financial and legal affairs, bought her books, lace, and rings, had their portraits painted,62 and was involved in the minutiae of her domestic life, even ordering food and supplies.63

Here I want to emphasize the public intertwining of their lives and ideas and the effect this must have had on Sir Francis, young Francis, his tutor Coste, and Esther. After Locke’s death, a myth of the couple’s idyllic life of the mind circulated and grew. Even at his death, it was said, Damaris was reading him psalms.64 Yet Esther was at his deathbed too. In contrast to other sources, her eyewitness account insists that Locke died on a close stool and that he closed his own eyes. Esther “heard him say the night before he died, that he heartily thanked God . . . above all for his redemption of him by Jesus Christ.” Esther’s account also reveals the tension that existed between Damaris and her stepdaughter.65

Yet in Locke’s will Esther received only a perfunctory ten pounds for mourning, though he knew she needed a dowry. There was no memento or book. Sir Francis was left ten pounds and some furniture from Locke’s rooms. In fact, Locke’s will was dominated by his affection for Damaris and his desire to make her independent of Sir Francis. Damaris and her son received Locke’s most intimate possessions. To Damaris went his rings, her choice of his books, and ten pounds for the poor to give “as she sees fit . . . and not account to anyone for the same,” a symbolic statement of her independence.66 Her son Francis received three thousand pounds, portraits of Locke and Damaris, cherished silver legacies, Locke’s silver screen “to preserve the eyes in reading,” and his clock. Finally, young Francis and Locke’s cousin Peter King each received half of Locke’s vast library. In secret letters, Locke instructed his executors to keep all of young Francis’s money free from his father’s control. “If decency had not forbidden it,” Locke admitted, “I should have put it into my will myself.”67 Less than a month after Locke’s death, Esther’s brother, writing from Lisbon, knew every detail of the will. He was “surprized when I heard he had left y[o]u only ten pound to buy y[o]u mourning. I had thought,” he remarked, that “you had been more in his books.” Surely Esther must have thought so too.68

There is little written evidence of why Damaris married Sir Francis. It is apparent, though, that in the absence of a proposal from Locke, only her marriage to another made it possible for her to live with him.69 Scholars agree that Sir Francis was passive and uninteresting.70 In the vast sea of Locke’s papers there is little mention of Sir Francis, though Locke wrote disapprovingly of his business dealings.71 Sir Francis died in 1723, four years before Esther, and assigned her two thousand pounds after debts. With the state of his finances, it would have been surprising if any money remained for her. By this time Esther was approaching fifty and unlikely to marry.72

Locke’s own correspondence, however, reveals at least one ardent suitor, Thomas Burnett of Kemney, a cousin of Archbishop Gilbert Burnet and a friend of Leibnitz.73 Burnett confided to Locke that Esther’s “transcendent qualities . . . wold charme any That is even lesse suceptible off impressiones from femelle perfectiones then my self.” Locke had already commissioned their wedding gift when Sir Francis turned down the offer, causing embarrassment to Esther.74 A cousin later inquired about her “Dutchman,” possibly Arendt Furly, son of Locke’s friend from Rotterdam, Benjamin Furly. In 1701–1702 Arendt was a guest at Oates, and “the young Hollander fell more into the company of Esther, daughter of Sir Francis Masham, along with Shaftesbury, and VonLimborch’s son.” This implies Esther’s participation in an elite circle of young intellectuals.75

In 1722, she looked back on her life and began to transcribe her letters.76 As we have seen, they contain valuable material about her family as well as the nature of family relations, including stepfamilies, about which little has been written. Nevertheless, it is Esther’s epistolary silences that provide the most important clues about how she wanted society to perceive her, her views regarding authorship, and her definition of private and public space.

In light of Esther’s family history, we can now view her letter book as the construction of her personal identity as she saw it. Although she used other people’s words, she told her own story in a way that preserved her modesty and fit accepted gender roles.77 Esther’s epistolary agenda had several central objectives. She wanted to present her own version of the history of the Masham family. This story would not be subsumed under the glaring publicity of the relationship between Locke and Damaris. Nor would it be linked to Queen Anne and Esther’s sister-in-law Abigail, that “dirty chamber maid” vilified in satiric verse.78 Though Esther included none of her own letters, she annotated those of others with a flood of marginalia and footnotes. Each note forms a little biography of a beloved family member (see illustrations, pp. 16–19). When linked together, they create her own Masham family tree. In Esther’s version her father’s first, little-known family is privileged. Her educated and cultured relations were good Protestants. She took pride in her brothers and felt their anguish far from home, fighting against kin, portionless like herself, and displaced from family.79 In a time of great anti-French sentiment, she wanted to reveal the sufferings of her French relations, especially their sacrifices for Protestantism. By choosing only complimentary letters, as noted above, she trained a positive spotlight on herself and her father’s first family. Similarly, her selection of Locke’s letters highlighted her intimacy with him and his high estimation of her character and intelligence.

She accomplished all of this on her own terms, in a way that did not violate the norms of gender and class but at the same time defined her own notions of public and private space. As Ezell has shown, “our definitions of ‘public’ and ‘private’ sit awkwardly with... the readership of manuscript texts.” We usually “use ‘public’ in the sense of ‘published’ and ‘private’ in the sense of ‘personal.’” But early modern manuscript culture by its very nature was “permeated by ‘public’ moments of readership, when the text was circulated and copied.” Though not available for purchase by readers, the text engaged in a “‘social’ function,” and was public in that regard.80 Esther was creating her album at a time when circles of manuscript exchange were still prevalent. In fact, she and other women like her were living, as Elizabeth Cook has put it, “at the crossroads of public and private, manuscript and print.”81 It is this crossroads that I explore in the following sections.

It is not surprising that for Esther, having a “voice” was not associated with print.82 Women like Esther would have seen no social cachet in a literary career and would have viewed manuscript as a more natural and prestigious mode than print.83 As recent studies have shown, the emphasis on print has obscured the fact that manuscripts coexisted with print, and indeed for many were the preferred and safest way to circulate one’s ideas. They were also economical, requiring no high investment initially, functioning, as D. F. McKenzie noted, more like “a bespoke trade: one-off or several copies could be done on demand.”84 In contrast, print technology was often linked with distorted and bad copies, to say nothing of corruption of texts and the misrepresentation of authors’ intentions. The experiences of Katherine Phillips and Lady Mary Chudleigh bear witness to the fear of such distortions, whether or not they intended to publish their works.85 Our own generation’s experience with computers and e-mail reminds us that new technologies are often attended by resistance or mistrust.

But if print was not an option, Esther and women like her found ways to make their books acceptable to themselves and to others. As Elaine Hobby demonstrates, women used a “repertoire of devices” to make their writing a “modest” act.86 Esther’s strategy in this regard was to become an editor of other people’s writing. This tactic suited her character as well as her times. It was, nonetheless, an astute way of obtaining agency and control over what would be known about herself and her family. Once we understand this, the justifications and apologies of her obligatory preface make sense. We see the same principle at work in the writings of other women, even expressed in the same words. Lady Mary Chudleigh, for example, claimed that her poems were written “for the innocent amusement of a solitary life.”87

I believe that in copying her letters, Esther was taking steps to “publish” her book in the contemporary sense of the term. Though a printed work was not intended, Esther did not deny the possibility that it might be placed in the public sphere. She was a typical representative of an age in which people spent much of their leisure time copying passages into commonplace books, journals, and diaries as well as letter books. Indeed, as Harold Love comments, copying was “almost universal among the educated.”88 Lisa Jardine contends that copying was viewed positively as an “attempt to give meaning to the scattered incidents of an individual life.” To copy had “richer connotations than mere reproduction, imitation, or mimicry in our modern, generally derogatory sense” because the copier was aspiring “to a meaning which might in itself be carried forward to become, in its own turn, the basis for future emulation.”89 Esther knew that once a letter was copied, it could reach a wider audience, regardless of the intent of the original writer. She engaged in that very process by duplicating mail addressed only to her.

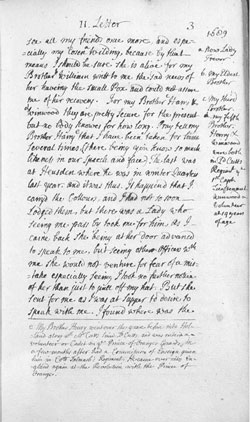

Letters from Relations and Friends to Esther Masham, Book 1, 1722 (Newberry Library, Case MS E5.M3827) pp. 2–3. Copy of a letter to Esther Masham, 8 July 1689, from her brother John in Flanders. Esther’s footnotes give biographical information about her brothers.

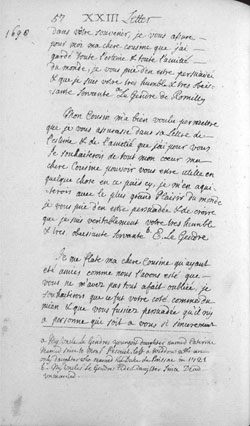

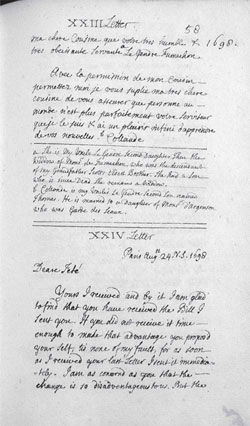

Esther’s letter book, pp. 57–58. Copies of parts of letters to Esther Masham, July and August 1698, from her brother Henry in France. Esther’s footnotes identify French relatives who have added postscripts to letter XXIII. These illustrations produced by permission of the Newberry Library.

In this time of transition and ambivalence toward publication, most people expected to encounter a spectrum of audiences, and Esther was no exception.90 At one end of the spectrum lay a letter written to a single addressee. It could soon move effortlessly through multiple readings and copies to include a larger audience of family and friends. Circles might then become more widespread and specialized, spreading, for example, to the court or the republic of letters. At the far end of the spectrum, manuscripts were printed publicly, with or without the author’s name, and with or without their consent. By 1737, Alexander Pope had broken with tradition by contriving to have his letters published while he was alive. But the mass audience at the spectrum’s extreme end was still abhorred by most writers, especially when the people cited were still living. Thus Phillips complained, perhaps disingenuously, that she could not “so much as think in private,” but must have her “imaginations rifled and expos’d to play the Mountebanks, and dance upon the Ropes to entertain all the Rabble . . . and to be the Sport of Some that can, and Some that cannot read a Verse.”91 With this wealth of options, it was and is difficult to know which type of audience was intended for any one text. In Esther’s case, though her book was ostensibly designed to remain a family heirloom, I believe she foresaw a larger group of readers. Why else would she bother to add notes that explained how people were related—facts that she already knew? And why write a preface to the reader, if there was none?

The view that Esther was attempting to “publish” her book is strengthened when we look at her album as a material object. Esther clearly had a printed book in mind when she created it. She started by making an ornamental title page. Then she wrote a preface, numbered her pages, added marginalia and footnotes, and helpfully appended an index. Once she started copying onto the blank pages, I believe she saw herself as an author. There were many authorial decisions to make as she looked back on her life. The letters had to be carefully read, sorted, selected, and arranged in a readable manner.92 Some letters had to be burned for the protection of friends and family. “Had the thought of Doeing this come into my head sooner,” she admitted, “I should have preserv’d some Letters I greive I have destroy’d.” Other letters might have just a few offending passages that could be rephrased or omitted. Esther was at perfect liberty to edit her own letters and to give them new shapes. Without the originals, there is no way of documenting exactly how much liberty she took. We do know, however, that when Mary Wortley Montagu compiled and transcribed her Turkish letters into an album, she labeled them “copies,” though they were extracts from lost journals and revisions of actual letters. “The letters,” notes her biographer, “are neither actual nor artificial, but something of both; altogether they are virtuoso letters in which she exploited her rich opportunities.”93

The question of the authenticity of Esther’s letters leads us to a final likely motive for “publishing” her book. In 1722, Esther knew that Locke’s letters were being sought for publication. Three English collections had already been published in 1708, 1714, and 1720. Calls for “authentic” material had been issued for future editions, and more works would appear to meet market demand.94 Living as she did in close connection to Locke’s publishers and the London literary market, she was aware of developments in the publishing world tied to the decline of patronage, the rise of commercial values, and changes in licensing and copyright, including controversy over piracy and forgery.95 This quiet spinster possessed authentic letters from the great philosopher that, moreover, showed her intimacy with him. But the method in which she chose to use them stood in stark contrast to the path taken by her stepmother.

Unlike Esther, Damaris flouted norms of gender and class in regard to her relationship with Locke as well as to her own writings. In contrast to her stepdaughter, she wanted to participate publicly in the intellectual arguments of her day. “Perhaps you may see me in Print in a little While,” she wrote Locke in 1685, “it being growne much the Fasion of late for our sex, Though I confess it has not much of my Approbation because (Principally) the Mode is for one to Dye First.” Perhaps Damaris was alluding to Anne Killigrew’s recently published poems.“At this time,” she continued, “I have no Great Inclination That Way . . . But I am not without some Apprehensions that I am to do so in A little Time.” Soon pregnancy, she realized, would keep her “settled in for a Pretty while.”96

In the 1690s, Damaris did indeed decide to publish her work anonymously. She plunged into the middle of a public debate between John Norris, Mary Astell, and Locke. In 1695, Mary Astell published Letters Concerning the Love of God, which many thought to be by Lady Masham. To prove it was not, Damaris “rushed into print” with a fierce rebuttal entitled Discourse Concerning the Love of God, which many assumed was written by Locke. Astell waited until Locke’s death to publish her own response, The Christian Religion as Profess’d by a Daughter of the Church of England. Damaris passionately replied to it in her widely read Occasional Thoughts in Reference to a Vertuous or Christian Life.97 Clearly Damaris occupied a different position on the spectrum of attitudes toward authorship than Esther did.

In her preface to Occasional Thoughts, Damaris made conventional apologies to cover her bold actions, but added unconventional qualifications. She had written it “some Years since, not without the thought that, possibly, it might be of farther use than for the entertainment of the Writer: Yet so little express Intention was there of Publishing the Product of those leisure Hours . . . that these Papers lay by for above two Years unread.” It was only after friends judged them “capable to be useful” that she sent them into the world. “I shall not repent the Publishing them,” she declared, if she could lead “one single Soul into the Paths of Virtue.” In a strong personal defense she added, “Modesty or Fear of Displeasing any” should not deter publication.98 Damaris’s attitudes toward authorship and publicity differed from those of Esther, and her public notoriety extended to her relations with Locke. Damaris and Mary Astell both claimed public spaces for their ideas. Even though Damaris did not sign her work, her behavior shows that norms were changing. Damaris and Esther were surely cut from different cloth.

Although they used different strategies of authorship, however, both women were viewed by others as having intellectual gifts. We see this clearly in seven intimate letters from Pierre Coste to Esther. They force us once again to reconsider Esther’s motives. Coste and other Huguenots have received great credit for introducing Continental ideas into England and English ideas into Continental Europe. Coste was made a member of the Royal Society in appreciation of his role as a translator. A confidante of Locke, he became an elite member of the republic of letters. Esther’s album reveals that she and Coste in fact had their own close epistolary relationship. Like Locke and Damaris, the pair exchanged books and had intense discussions about classical writers, especially Horace. Coste wrote to Esther about his work, sent proofs, and asked for her comments.99 Just as Locke and Damaris were intellectual soul mates, so Coste addressed Esther as both a close associate and an intellectual confidante.

A friend of Coste’s commented on their friendship shortly after Damaris’s death: though Coste had lost an excellent friend in Lady Masham, he still had “so near a relation and friend of hers left in ye same degree of friendship and as capable of it as she was.”100 In a rare outburst of authorship, Esther underlined this complimentary passage that referred to her talents. Esther’s aspirations may have been more modest than those of Damaris, who wished to participate in intellectual debates. Yet I believe Esther wished to have an audience larger than her own family, one that did not already know the facts set out in her footnotes. At the end of her life, this solitary spinster had no descendants to carry on her memory or enshrine her reputation. Her letter book would accomplish that task.

Coste and Esther shared another bond. They had both essentially been left out of Locke’s will. The correspondence of Pierre Desmaizeaux reveals disagreements between Coste and Locke arising from alleged criticisms Coste expressed in his translations. In 1720, a preface to a collection of Locke’s papers publicly castigated Coste for “blackening” Locke’s character. Yet others disagreed. Charles de la Motte, for example, thought Locke’s treatment of Coste was shocking. Esther’s letter book subtly confirms these tensions, though, as Anne Goldgar notes, we have no definite evidence describing their quarrel.101 Esther would have been one of the few witnesses to such a dispute and she would have known about allegations against Coste. Her album, nonetheless, presents Coste in a positive light. At the time of Coste’s letters to Esther, a new edition of Locke’s letters was being published. Coste refers to the fact that Esther had seen it. He had heard, he wrote her, that it contained only complimentary and boring Latin letters, and though he had made suggestions, his advice had not been followed.102 It seems that Esther had many reasons to reveal Coste’s letters, and not just because they identified her as a learned lady with a place in the republic of letters. In contrast to other letter collections produced by a voracious commercial press, her letter book offered authentic manuscript letters that had never been seen before. It proclaimed her ownership of Locke’s letters and her place in his life. It also shows us that female authorial agency might be achieved in subtle and indirect ways.

In addition to contemporary perceptions of authorship, Esther’s letter book raises general issues about the use of letters as historical and literary evidence. Letter collections in general can help us to make connections between “big” and “little” history. As we set aside grand theories and meta-narratives, letters become even more important methodologically. Historians and literary critics must find ways to integrate the great and the ordinary so that micro-studies may be placed in a wider context and impart larger meaning. Because letters are themselves links in an ongoing chain, they show patterns over time and reveal networks. If you read letters of important people, their friends and family will creep in. And if you read letters of ordinary people, luminaries will surely appear. When Esther is placed in the larger world of Locke, Damaris, and Coste, her simple life expands. At the same time, her letters place Locke the man in her world, showing his personal relations, his frailties and strengths, and the impact of his bequests. Everyday experiences found in Locke’s letters take on added dimensions when viewed from Esther’s perspective.

Personal correspondence as a genre frequently presents the great and the ordinary as they coexist and interact side by side. In 1704, Locke told Anthony Collins how much he enjoyed their correspondence. They might discuss truth and friendship or “descend to a brush or a curry-comb, or other such trumpery of life.” Locke felt blessed “in such a friend, with whom I can converse and be enlighten’d about the highest speculations, and yet be assisted by in the most trivial occasions.” The latter included Collins’s intense interest when reporting a purchase of shoe buckles for Locke.103 A day in Locke’s life in which he wrote nothing but letters may have been a day of importance for his ideas. In fact, Locke’s great works abound with familiar examples from domestic life. They often start with a question arising from daily experience, followed by careful observation. Sometimes they are written in the first person, with current observations that invite the reader’s response, as in a letter.104

Some Thoughts on Education, for example, arose from real letters to two perplexed parents. The letters proposed new educational methods based on actual domestic situations. “How many of these situations were witnessed by him,” wrote John and Jean S. Yolton, “or whether he actually was able to apply, or to get parents to try, the methods he recommends, we do not know.” Letters to and from Esther and Damaris’s son Francis (Frank), however, show this very process in action. When Damaris and Sir Francis allowed Locke to instruct both their children according to ideas in Some Thoughts on Education, he was able to put theory into practice.105 Thus, when Locke instructed young Frank, he combined sternness and affection. He lured him into learning by requiring effort in return for praise. “Assure [Frank] that I love him very much,” Locke wrote Esther, “but I expect to heare from him some news of what he saw or observ’d at the Assizes.” He was instructing the boy in the same method of careful observation that he used in his own writing. As Locke observed Frank, he was documenting his theory that knowledge is gained experientially by the senses, making its mark on the mind as on a tabula rasa.106

Francis’s reply to Locke reveals a child, not yet seven, who was trained to think and observe: “I went . . . on the bench, which was very full, and heard the Judges speech . . . I thought it was a very noble office to be a Judge, but not a very easie one. I think it is a serious thing to condemn people to death. I saw some burnt in the hand & some in the cheek. I thought it very moveing to see the poore prisoners when they were condemned fall down upon their knees beging pardon or transportation. When my Lord gave sentence he said, since you have lived as the Theif who was crucified with our blessed Saviour I hope you will repent like him at your deaths.”107 Surely this “little” incident gives us data about attitudes to “big” topics such as crime, education, and law, as well as Locke’s social relationships and their effects on his work.

In a similar fashion, Esther’s album helps us to see larger national trends regarding the development of letter writing. Because it is bilingual, her book reveals cultural differences, and these are highlighted by presenting French and English letters on the same page. As noted earlier, they juxtapose different notions of politeness at work. This case study suggests that though France and England borrowed epistolary models from Renaissance courts, letter writing evolved differently in the two countries. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, classical and French manuals were duly copied and followed in England. By the 1680s, however, English letters overflowed with complaints about flattery and ceremony, including those made by Locke. In 1704 he warned Anthony Collins that he would not send him “anything that looks like a complement.” Write to me, he begged, “with as little ceremony and scruple as you see I use with you.”108 The desire for more natural forms of self-expression was evident as a culture of politeness developed. English gentry wished to cease “sending young gentlemen . . . into France to learn manners . . . They come back fool as ever, imitating the French mode with so much affectation . . . that in derision we Englishmen are justly styled apes of the French.”109

These feelings were linked to cultural differences regarding politics and religion, as well as social relationships. In the aftermath of the Revolution Settlement in 1688, constant Continental wars fanned the flames of English hostility toward French absolutism. Lawrence Klein has shown how this anti-French sentiment was connected to sociability and politeness. French foppishness and exaggerated manners became symbols of all that the English detested. Yet the English desire for French refinement coexisted with a hatred of French dominance. “We are the nation they pay the greatest civilities to, and yet love the least,” wrote a French observer. “They condemn, and yet imitate us.”110

These anxieties were clearly evident when it came to letter writing. It is not surprising that English letter writing became focused on the family, not the corrupt court or effeminate salon that preoccupied French epistolary culture. After 1700, English epistolary imitation of French models became less prevalent. The advent of more commercially oriented letter-writing manuals and the spread of letter writing to the middling sort hastened this trend. By the mid-eighteenth century, as imperial power grew, British epistolary culture was increasingly shaped by the trading classes. Their confident, flowing, copper-plate hand was now imitated by others. Eventually it would become dominant around the world.111

This national comparison reminds us of the complexity of factors influencing epistolary production. Letters are not simple, transparent texts. They come in many states—originals, drafts, and copies in letter books or collections. Often they tell the same story from different points of view. Readers must not expect a simple correlation between expressed statements and lived experience. Even transcribers like Esther formulate a pose and erect a screen in order to present the self positively, adding another layer of purposeful interference. Sometimes they leave out pertinent material but furnish clues; other times they exaggerate or tell a white lie. Some letters are windows into the soul marked by truth-telling; others are highly crafted pieces of convention. Usually, they are a blend of both.

It is generally accepted that we must analyze letters in the context of their literary and historical culture. Less apparent is the necessity to listen for epistolary silences. In Esther’s case, omissions provide signals that attitudes toward authorship were changing, along with notions of public and private space. Gaps in her evidence make us reconsider what was a publication and who was an author in her time. Instead of simple dichotomies we find a spectrum of motives, authors, and audiences. Esther and Damaris occupied different positions on that spectrum, though both were elite women. While gender and class norms were extremely important, they were also under going change.

It is impossible to discover how many people actually read Esther’s album. Locke’s biographer Fox Bourne, however, examined it before 1876. “Esther Masham,” he remarked, “has nearly as important a place in Locke’s biography as Lady [Damaris] Masham herself.” After reading the same letter book, A. C. Fraser concluded that Esther was “Locke’s favourite companion.” “Locke’s admirers,” he continued, “owe something to Esther Masham.” In her book, “the fresh and lively details of the most commonplace incidents . . . make the family, with Locke as its principal figure, live again.” Esther was also known to the antiquarian Philip Morant, Rector of St. Mary’s Colchester and fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, by the time he published The History and Antiquities of the County of Essex in 1768. After describing Oates, he glossed quickly over the life of her father, Sir Francis. “His daughter who outlived him,” noted Morant, “was a lady of great accomplishments.”112 His view of Esther was the very one that she had constructed for herself. Though we will never know for certain, it is possible that Morant had read her letter book as well. Our own reading of the letters is yet another chapter in the ongoing history of Esther’s life and reputation. Although she never published anything in the modern sense of the word, she has now become an author, after all.

I thank Frances Harris for leading me to Esther’s letter book and Sonia Anderson, Betsy Brown, Elizabeth Clarke, Nicholas Cronk, Mark Goldie, Mark Knights, Peter Lake, and Moshe Sluhovsky for commenting on drafts of this article. The audiences for papers given at Princeton University (1999), the North American Conference on British Studies (1999), and King’s College, University of London (2001), gave me helpful ideas. This article originally appeared in the Huntington Library Quarterly. 66:3&4 (2004), 275–305.

Susan Whyman is the author of Sociability and Power in Late-Stuart England: The Cultural Worlds of the Verneys, 1660–1720 (1999), and Pen and the People: English Letter Writers 1660–1800 (2009), winner of the 2010 Modern Language Association Prize for Independent Scholars. She has also edited, with Clare Brant, Walking the Streets of Eighteenth-Century London: John Gay’s “Trivia” (2009).

— Susan Whyman

1 Newberry Library, Case MS E5.M 3827, Letters from Relations and Friends to Esther Masham, Book 1, 1722 (hereafter “LB”), title page and preface. I have also consulted Bodleian Library, MS Facs. e. 54, Copy of Esther Masham’s Letter Book. I thank the Newberry Library for granting permission to quote from the manuscript. I refer to Esther’s letter numbers instead of folio numbers, which are not always consecutive in the original; in the Bodleian copy, folios have been renumbered.

2 Locke’s letters are LB 4, Oates, 23 July 1694; LB 5, Oates, 20 August 1694; LB 6, London, 2 October 1694; LB 8, London, 8 December 1694; LB 10, 1696; LB 11, London, 1 September 1696; LB 13, London, 24 August 1697; LB 15, London, 13 October 1697; LB 19, Oates, 29 April 1698; LB 35, London, 21 July 1699; LB 36, London, 27 July 1699; attachment to LB 67, Oates, 7 November 1701, from Esther’s stepbrother Francis Cudworth Masham (Frank).

3 The Newberry Library has only one volume; presumably the second was lost. See A. C. Fraser, Locke (1890; London, 1970), 215–216; and H. R. Fox Bourne, The Life of John Locke, 2 vols. (London, 1876), 2:298–301, 454–457, 461, 475–476, 493.

4 M. Cranston, “John Locke’s Correspondence with Esther Masham,” Newberry Library Bulletin, 2d ser., no. 4 (1950): 121–135.

5 The Correspondence of John Locke, ed. E. S. De Beer, 8 vols. (Oxford, 1976–1989); citations are to volume and letter number: vol. 2, no. 837 (p. 758, n. 1); vol. 5, nos. 1758, 1769, 1773, 1795, 1825, 1983, 2124; vol. 6, nos. 2301, 2327, 2426, 2603, 2607; vol. 7, nos. 3003, 3028.

6 P. Long, A Summary Catalogue of the Lovelace Collection of the Papers of John Locke in the Bodleian Library (Oxford, 1959), 13; Bodl., MS Locke c.16, fol. 3, Brompton, 7 August 1694; fols. 4–5, London, 20 September 1701, in both French and English, concerns a Monsieur Pelletier of Rouen, about whom Locke wanted information. For Jean de la Pelletier, see Noel d’Argonne (pseudonym M.de Vigneul-Marville), Melanges d’histoire et de Litterature, vol. 1 (Rotterdam, 1700), 105–118. Locke later purchased his Dissertations sur l’arche de Noe et sur l’Hemine et la livre de St. Benoist (Rouen, 17[00]). See John Harrison and Peter Laslett, The Library of John Locke , 2d ed. (Oxford, 1971), 205, #2246; and Bodl., MS Locke c.35, “List of Books Left to Peter King by John Locke,” #46.

7 For another set of letter books, see Frances Harris, “The Letterbooks of Mary Evelyn,” English Manuscript Studies (1998): 202–215.

8 See Carolyn Steedman, “A Woman Writing a Letter,” in Rebecca Earle, ed., Epistolary Selves: Letters and Letter-Writers, 1600–1945 (Aldershot, UK, 1999), 121; Mary A. Favret, Romantic Correspondence: Women, Politics, and the Fiction of Letters (Cambridge, 1993), 21; and Elizabeth C. Goldsmith and Dena Goodman, eds., Going Public: Women and Publishing in Early Modern France (Ithaca, N.Y., 1995).

9 The Selected Letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, ed.Robert Halsband (London, 1970), 3.

10 Ingrid Tague, Women of Quality: Accepting and Contesting Ideals of Femininity in England, 1690–1760 (Woodbridge, UK, 2002), passim.

11 Quoted in Ruth Perry, The Celebrated Mary Astell (Chicago and London, 1986), 109.

12 Margaret Ezell, Social Authorship and the Advent of Print (Baltimore and London, 1999), 38–39. The Perdita Project has now uncovered the writings of a vast number of women and the secondary literature is huge and growing.

13 Susan Whyman, “‘Paper Visits’: The Post-Restoration Letter as Seen through the Verney Family Archive,” in Earle, ed. Epistolary Selves, 15 and The Pen and the People (Oxford, 2009)

14 For a new view of English literacy in the long eighteenth century see The Pen and the People.

15 Susan Whyman, “A Passion for the Post,” History Today, December (2009), 33–39. The Post Office: An Historical Summary (London, 1911); Philip Beale, History of the Post in England from the Romans to the Stuarts (Aldershot, UK, 1998); and H. Robinson, The British Post Office: A History (Princeton, N.J., 1948). In “Postal Censorship in England, 1653–1844,” a paper delivered at the Censorship Conference at the Center for the Study of the Book, Princeton University (27 September 2003), I consider these issues based on records in the Post Office Archive, London; see http://web.princeton.edu/sites/english/csbm.

16 Lady Sarah Cowper, for example, in the early eighteenth century, would “read the Spectator and Scribble every morning from eight o’clock to noon”; see Anne Kugler, Errant Plagiary: The Life and Writing of Lady Sarah Cowper, 1644–1720 (Stanford, Calif., 2002), 183.

17 For example, Berkshire Record Office, D/EE Masham Family Papers, fols. 28–42, including fol.35, will of Sir Francis Masham, 1 January 1718/9; fol. 36, will of Francis Cudworth Masham; fol. 40, genealogical notes of the Masham family, ca. 1760; fol. 41, Masham family pedigree, ca. 1725; Essex Record Office, D/DEw, Estate and Family Papers; G. E. C., The Complete Baronetage (Gloucester, 1983), 3:14–15; Thomas Wotton, The Baronetage of England (London, 1771), 2:1–3. For other Masham family wills, see n. 19 below.

18 Jean S. Yolton, ed., A Locke Miscellany (Bristol, 1990), 332 (illus.); Fraser, Locke, 215–16; Peter Laslett, “Masham of Oates: The Rise and Fall of an English Family,” History Today 3 (1953): 535–543.

19 PROB 11/590/55, Essex Will of Sir Francis Masham, d. 1723; PROB 11/645/157, Will of Francis Cudworth Masham, d. 1731; PROB 6/103, Essex Administration, Esther Masham, d. 1727; PROB 11/340, film 841, Samuel Baron Oates, d. 1758; PROB 6/77, Middlesex Administration, William Masham, d.1701; PROB 11/511/224, Hants Will of John Masham, d. 1709; PROB 6/85, Middlesex Administration, Winwood Masham, d. 1709; Philip Morant, The History and Antiquities of the County of Essex, 2 vols. (London, 1768), 1:141. Bodl., Gough Essex 31 and 32, published in 1761, contain supplementary documents including sale of the Oates estate and a subscription proposal; see De Beer, Correspondence, vol. 2, no. 837, Damaris Masham to John Locke, 14 November [1685]. I thank Mary Clayton for many of these references.

20 See Ross Hutchinson, Locke in France (Oxford, 1991), 1–41; John Lough, Locke’s Travels in France, 1675–1679 (Cambridge, 1984); and Sheryl O’Donnell, “‘My Idea in Your Mind’: John Locke and Damaris Cudworth Masham,” in R. Perry and M. Watson, eds., Mothering the Mind (New York, 1984), 40.

21 Laslett, “Masham of Oates,” 537; Fox Bourne, Life of Locke, 2:212.

22 Laslett, “Masham of Oates,” 537–538.

23 BL, MS Add. 4290, fol. 66, John Locke, Oates, 23 December [1692]; De Beer, Correspondence, vol. 4, no. 1580, John Locke to Edward Clarke, 23 December [1692]; Fox Bourne, Life of Locke, 2:251.

24 Morant, History of Essex, 1:141.

25 E. Cruickshanks, S. Handley, and D. Hayton, The House of Commons, 1690–1715 , vol. 4 (Cambridge, 2002), 765–768. He was M.P. for Essex, 1690–1698 and 1701–1710.

26 François Farin, Historie de la ville de Rouen par un solitaire & revue par plusieurs personnes de merite, 3d ed. (Rouen, 1732); “seconde partie contenant la noblesse” refers to many of the surnames in Esther’s letters. For the enoblement of her grandfather Guillaume Scott in 1664 and Thomas Le Gendre in 1685, see p. 15; others of the Le Gendre family, 75, 154; Pelletier, 70, 154, 173; Jacques du Hamel, 13. See also The Traveller’s Guide to Rouen (Paris, 1830); Jules Fromentin, Rouen and the Environs (Rouen, 1898); and De Beer, Correspondence, vol. 5, no. 382, n. 1.

27 LB 1, Scott Le Gendre, 1686.

28 De Beer, Correspondence, vol. 2, no. 758. Esther was ten when she arrived in the summer of 1685. See Robin Gwynn, Huguenot Heritage: The History and Contribution of the Huguenots in Britain (London, 1985); Samuel Smiles, The Huguenots: Their Settlements, Churches, and Industries in England and Ireland (Baltimore, 1972). See also Henry Compton, Bishop of London, A Circular Letter to the Clergy . . . recommending their Care . . . for the French Protestants (London, 1686); and A Letter to the French Refugees Concerning Their Behavior to the Government (London, 1710).

29 De Beer, Correspondence, vol. 7, no. 3003, Esther Masham, 20 September 1701, p. 440n.

30 LB 3, William Masham, Breda, 20 December 1689, footnote on p. 7; LB 22, Henry Masham, Rouen, 7 July 1698; LB 38, C. de Drumare, London, 13 October 1699.

31 LB 32, C. de Drumare, 28 January 1698/9. On Huguenot persecution, see Richard Strutton, A True Relation of the Cruelties and Barbarities of the French upon the English Prisoners of War . . . With an account of the Great Charity and Sufferings of the Poor Protestants of France (London, 1690); François Bion, An Account of the Torments the French Protestants Endure aboard the Galleys (London, 1708); The Case of the Poor French Protestants [1700]; and Jean Claude, An Account of the Persecutions and Oppression of the Protestants (London, 1686).

32 LB 23, Henry Masham, Rouen, 30 July 1696; LB 60, C. de Drumare, 12 August 1701; LB 2, John Masham, “From the Camp,” 8 July 1689.

33 LB 122, Governour Poirier, St. Helena, 12 August 1706.

34 LB 50, Henry Masham, Charlemont, 14 January 1706.

35 LB 48, Scott de Drumare, Rouen, 18 December 1700.

36 LB 40, C. de Drumare, London, 13 February 1699/1700; LB 42, C. de Drumare, London, 17 May 1700; Madeleine de Scudery, Conversations upon Several Subjects (London, 1683); and Artamenes; or, the Grand Cyrus (London, 1690–1691).

37 LB 29, Scott Le Gendre, September 1698; LB 48, C. de Drumare, London, 13 October 1699; see also William Hull, Benjamin Furly and Quakerism in Rotterdam (Lancaster, Pa., 1941), 174–176.

38 Tamworth Reresby, trans., A Collection of Letters Extracted from the Most Celebrated French Authors (London, 1715) has double title pages and letters side by side in French and English, as in Esther’s book.

39 LB 23, 30 July 1698. See Terttu Nevalainen and Helena Raumolin-Brunberg, eds., Sociolinguistics and Language History: Studies Based on the Corpus of Early English Correspondence (Amsterdam, 1996), 6–9, 167–180; and J. B. Pride and Janet Holmes, Sociolinguistics: Selected Readings (Harmondsworth, UK, 1972).

40 LB 135, A. Masham, Kensington, 8 December 1707.

41 LB 121, Charles Masham, St. Helena, 1 September 1705.

42 De Beer, Correspondence, vol. 3, no. 1003, Damaris Masham, 5 (?) February [1688]. On p. 357, n.2 refers to Henry (d. 1702) as “A Son of Mine, who has leave to be in England for Two Months who should bring you my next [letter],” and again in vol. 3, no. 1040, 7 April 1688 (pp. 434–435): “He is one I should be very loath to lose . . . [post script]: “You would find [him] a very Honest Gentleman . . . And Much Better Company then most Young Gentlemen of His Profession . . . You will wonder at first I suppose to find a Son of Mine So little an English Man as I do at your little Gentlemens speakeing French.”

43 LB 22, Henry Masham, Rouen, 7 July 1698; LB 28, T. Gale (Galle), 27 September 1698; Bodl., MS Locke c.16, fols. 1–2, Charles Masham to John Locke, n.d.;LB 38, C. de Drumare, London, 13 October 1699. Her grandfather had left 1,000 livres and her grandmother 2,500 but owing to terms of the will Esther could not obtain her legacies. Some of her inheritance reverted to her brothers if she died unmarried.

44 Jean de la Bruyere, The Characters, or the Manners of the Age . . . With the Characters of Theophrastus . . . To which is added a Key to his Characters (London, 1699). Locke owned three copies, numbered 505–506, 586, and 2887 in Harrison and Laslett, Library of Locke, 95–96, 100, 247. In BL, MS Add. 4290, fol. 13, “Mr. Locke’s Extempore Advice,” Locke calls La Bruyere’s Characters “an admirable piece of painting.” See also Jean S. Yolton, Locke: A Descriptive Bibliography (Bristol, 1998), 217–218, n.169; and John Locke, Some Thoughts on Education, 5th ed., 1705. In paragraph 195 of this edition, Locke inserted a long quotation from La Bruyere’s Caracteres, ou Moeurs de ce siecle , to which was appended Les Caracteres de Theophraste (1696). See LB 22, Henry Masham, Rouen, 7 July 1698; LB 23, Henry Masham, Rouen, 30 July 1698; LB 24, Henry Masham, 24 August 1698; LB 25, Henry Masham, Paris, 12 September 1698; and Fraser, Locke, 223.

45 LB 25, Henry Masham, Paris, 12 September 1698.

46 LB 22, Henry Masham, Paris, 7 July 1698; LB 23, Henry Masham, Rouen, 30 July 1698.

47 PROB/11/840/340, will of Samuel Masham; LB 128, Samuel Masham, London, 25 September 1707; DNB (1917), 12:1296–1297. The Reasons which induced Her Majesty to Create Samuel Massam Esq; Peer of Great Britain (London, 1712); Mr. G., Minister of C., The Tryal of skill, performed in Essex at the Election of Colonel Mildmay and S. F. Masham (Chelmsford?, 1689); E. Cruickshanks, House of Commons, 4:768–769.

48 LB 124, Samuel Masham, Chester, 16 June 1707; LB 80, Alix Compton and Jenny Knight, London, 2 May 1702.

49 See seven pages of notes appended to the original album by an earlier indignant reader who erroneously thought they were love letters. Many books that were referred to in Esther’s letters appear in Locke’s library catalogue, account books, and footnotes to his works. Esther appears in references to daily life in the Lovelace collection of Locke’s papers. For example, Bodl., MS Locke c.1, fol. 332, 26 January 1697; fol. 333, 20 July 1697; fol. 337, 18 August 1698.

50 In Bodl., MS Locke c.16, fol. 3, she closes with the phase: “your Landabridis is Faithfully Yours.” In MS Locke c.16, fols. 4–5, she is “your very much obliged and most affectionate Dib.” De Beer thinks it may be “an erroneous form of Lindabrides” (Correspondence, vol. 5, no. 1758, p. 85, n. 2). See D’Ortunez de Calahora, The Mirrour of Knighthood (London, 1599), 2:75ff.

51 LB 19, John Locke, Oates, 29 April 1698.

52 LB 13, John Locke, London, 24 August 1697.

53 As described in his letters in the letter book; see also Bodl, MS Locke c.16, fols. 3–5.

54 John Yolton and Jean Yolton, eds., Some Thoughts Concerning Education by John Locke (Oxford, 1989), 7, 22, 60–61; Bodl., MS Locke fol. 29, p. 145. Mrs. Masham and L. Masham are both on a list of presentation copies in his notebook headed “Education 95.” The Yoltons agree that one copy is for Lady Damaris and another for “Mistress Esther.”

55 LB 4, John Locke, Oates, 23 July 1694; LB 33, Scott Le Gendre, Rouen, 23 March 1699.

56 Fox Bourne, Life of Locke, 2:477–479. De Beer, Correspondence, vol. 2, nos. 470–472, contains a biography of Damaris and Sir Francis.

57 Bodl., MS Locke c.17, fols. 77–155, 1682–1688. See W. von Leyden, “Notes Concerning Papers of John Locke in the Lovelace Collection,” Philosophical Quarterly 2 (1952): 68–69; and indexes in DeBeer, Correspondence.

58 De Beer, Correspondence, vol. 2, no. 820, Mrs. Anna Grigg, 20 April 1685; O’Donnell, “Locke and Damaris Masham,” 34; Laslett, “Masham of Oates,” 536–537; DNB (1917), 12:1297–1298.

59 See Sheryl O’Donnell, “Mr. Locke and the Ladies: The Indelible Words on the Tabula Rasa,” Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture 8 (1979): 155; Sarah Hutton, “Damaris Cudworth, Lady Masham: Between Platonism and Enlightenment,” British Journal of History and Philosophy 1 (1993): 29–54; P.Springborg, “Astell, Masham, and Locke: Religion and Politics,” in Hilda Smith, ed., Women Writers and the Early Modern British Political Tradition (Cambridge, 1998), 105–125; and Springborg, ed., Mary Astell: Political Writings (Cambridge, 1996), xiv–xix. See also George Ballard, Memoirs of Several Ladies of Great Britain, who have been Celebrated for their Writings or Skill in the Learned Languages, Arts and Sciences (Oxford, 1752), 379–388.

60 Springborg, “Astell, Masham, and Locke,” 106–107, 113; Kathryn Ready, “Damaris Cudworth Masham, Catherine Trotter Cockburn, and the Feminist Legacy of Locke’s Theory of Personal Identity,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 35 (2002): 563–576; Lois Frankel, “Damaris Cudworth Masham: A Seventeenth-Century Feminist Philosopher,” in Linda L. McAlister, ed., Hypatia’s Daughters: Fifteen Hundred Years of Women Philosophers (Bloomington, Ind., and Indianapolis, 1996), 130; and Alan Cook, “Ladies in the Scientific Revolution,” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 51 (1997): 1–12.

61 The Reverend John Edwards, Locke’s critic, referred to the seraglio; see Bodl., MS Locke c.23, fols. 200–202, an anonymous letter to the Bookseller John Churchill, July 1697; Maurice Cranston, John Locke: A Biography (London, 1959), 215; and Harrison and Laslett, Library of Locke, 8.

62 De Beer, Correspondence, vol. 8, no. 3624, Locke to Anthony Collins, 11 September 1704; David Piper, Catalogue of Seventeenth-Century Prints in the National Portrait Gallery, 1625–1714 (Cambridge, 1963); De Beer, Correspondence, vol. 8, appendix 1.

63 For example, Bodl., MS Locke c.2, fols. 2–3, Locke’s Account Book, 1704; and MS Locke, f.10, fols. 179–180. See O’Donnell, “Mr. Locke and the Ladies,” 215; and “Locke and Damaris Masham,” 41.

64 [J. Le Clerc], An Account of the Life and Writings of John Locke Esq; 3d ed. (London, 1714), 22–23, 45–49.

65 BL, MS Add. 4311, correspondence of Thomas Birch, fols. 42–43, J. J. to T. Birch, Coventry, 25 August 1752, cover letter, with a letter attached from Esther Masham to “a person who had been a servant in the family” [Mrs. Smith], Oates, 17 November 1704. J. J. notes that the letter “was communicated lately by a Friend who took it from the original letter.” This is another instance in which an original, later lost, was copied.

66 Bodl., MS Locke b.5, item 14, copy; Yolton, ed., “The Last Will and Testament of John Locke, Esq.,” A Locke Miscellany, 353–364; De Beer, Correspondence, vol. 8, nos. 419–427.

67 BL, MS Add. 4290, Correspondence and Papers of John Locke, 1678–1704, fols. 1–2, John Locke to Anthony Collins, Oates, 23 August 1704, “to be delivered to him after my decease.”

68 LB 102, Samuel Masham, Lisbon, 25 November 1704.

69 O’Donnell, “Locke and Damaris Masham,” 39.

70 His “birth, marriage, and friendships qualified him for a place in political life that his personal achievements did not perhaps merit,” notes the DNB. See also E. Cruickshanks, House of Commons , 4:765–768. I thank Stuart Handley for notes on Sir Francis, who entered Parliament as a Whig. When his son Samuel married Abigail Hill, he became beholden to Tory interests. His committee work dealt with election practices, naturalization of immigrants, and recoinage, which were important issues for the Oates household.

71 De Beer, Correspondence, vol. 8, no. 3583, Locke to Peter King, Oates, 9 July 1704.

72 PROB 11/590/ 55; Essex Administration, PROB 6/103.

73 De Beer, Correspondence, vol. 6, no. 2228, Thomas Burnett of Kemney, 24 March 1697, and biographical note, p. 60. He married Elizabeth Brickenden in 1713; vol. 6, no. 2565, 17 March 1699. See W.von Leyden, “Papers of Locke in the Lovelace Collection,” 66–67; and J. Allardyce, ed., The Family of Burnett of Leys (New Spalding Club, 1901).

74 De Beer, Correspondence, vol. 7, no. 2710, Thomas Burnett, 13–14 April 1700, mentions his suit to Esther with a covering letter to Martha Lockhart, no. 2709, 15 April 1700; see also no. 2715, Martha Lockhart, 20 April 1700; and no. 2724, A. Locke to Thomas Burnett, 2 May 1700.

75 LB 86, Francis St. John, 12 November 1703, notes that her “Dutchman” has married and implies that she did not think him suitable; see LB 118, A[rendt] Furly, On Board the Ranelagh in Gibraltar Bay, 24 July 1705. See also William Hull, Benjamin Furly and Quakerism in Rotterdam, Swarthmore College Monographs on Quaker History, no. 5 (Lancaster, Pa., 1941), 170–177, esp. 174; and B. Rand, ed., Life and Letters of Anthony, Earl of Shaftesbury (London, 1900).

76 For another look at the autobiographical account of a Huguenot family, see Carolyn Lougee Chappell, “‘The Pains I Took to Save MY/His Family’: Escape Accounts by a Huguenot Mother and Daughter after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes,” French Historical Studies 22 (1999): 14.

77 See Carolyn Heilbrun, Writing a Woman’s Life (New York, 1988), 17–18.

78 The Prophesy: or, M-m’s [Mrs. Masham’s] Lamentation (London, 1710); A New Ballad. To the tune of Fair Rosamond (London, 1708), first stanza; John Dunton, King Abigail: or, the secret reign of the she-favourite [Abigail Masham] (London, 1715).

79 In the end, she would lose seven brothers, most of them in the service of England’s empire; LB58, Henry Masham, Charlemont, 21 June 1701; LB 122, Governour Poirier, St. Helena, 12 August 1706; Morant, History of Essex, 1:141.

80 See Ezell, Social Authorship, 38–39.

81 Elizabeth Cook, Epistolary Bodies, Gender and Genre in the Eighteenth-Century Republic of Letters (Stanford, Calif., 1996), 5.

82 See Ezell, Social Authorship, 43

83 I thank Betsy Brown for this insight.

84 84. D. F. McKenzie, “Speech, Manuscript and Print,” in New Directions in Textual Studies, ed. D. Oliphant and R. Bradford (Austin, Tex., 1990), 94.

85 Poems By the Most Deservedly admired Mrs. Katherine Phillips, the Matchless Orinda . . . with Several Other Translations out of French (London, 1705), Preface, dated 29 January 1663/4; Poems on Several Occasions together with the Song of the Three Children Paraphras’d by the Lady Chudleigh, 2d ed. (London, 1709), Preface. The current use of e-mail suggests a modern crossroads in which the epistolary genre is redrawing the boundaries of public and private communication. See also Walter Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word (London and New York, 1982).

86 Elaine Hobby, Virtue of Necessity: English Women’s Writing 1649–1688 (London, 1988), 1–2, 9.

87 Poems by the Lady Chudleigh, Preface, A4.

88 Harold Love, Scribal Publication in Seventeenth-Century England (Oxford, 1993), 40–41.

89 Lisa Jardine, Erasmus, Man of Letters: The Construction of Charisma in Print (Princeton, N.J., 1993), 59.

90 See Kathleen Grathwol, “Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and Mme de Sevigne,” Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century 332 (1995): 151; James Fitzmaurice and Martine Rey, “Letters by Women in England, the French Romance, and Dorothy Osborne,” in J. Brink et al., eds. The Politics of Gender in Early Modern Europe, Sixteenth-Century Essays and Studies, vol. 12 (Kirksville, Mo., 1989), 149–160.

91 Poems By . . . Katherine Phillips, Preface, A1v. See also James A. Winn, A Window in the Bosom: The Letters of Alexander Pope (Hamden, Conn., 1977), 34–39.

92 It was a time when many people organized their papers. For examples of compilers who felt like authors as they examined family papers, see Ezell, Social Authorship, 27–36.

93 Halsband, Selected Letters, 11–12.

94 Yolton, Locke: A Descriptive Bibliography , 385–397; John Locke, Some Familiar Letters between Mr. Locke, and Several of His Friends (London, 1708, and later editions), Preface; [Le Clerc], Account of the Life and Writings of John Locke Esq; [Pierre Desmaizeaux, ed.], A Collection of Several Pieces of Mr.John Locke, Never before Printed, or not Extant in his Works (London, [1720]); T. Forster, ed., Original Letters of John Locke, Algernon Sidney, and Anthony Lord Shaftesbury (London, 1830); J. and J. Yolton, Reference Guide.

95 See Brean S. Hammond, Professional Imaginative Writing in England, 1670–1740: Hackney for Bread (Oxford, 1997); Mark Rose, Authors and Owners: The Invention of Copyright (Cambridge, Mass., 1993), 27–30; and Dale Spender, ed., Living by the Pen: Early British Women Writers (New York, 1992).

96 De Beer, Correspondence, vol. 2, no. 839, Damaris Masham, 14 December 1685; Anne Killigrew, Poems (London, 1986). De Beer notes that though Killigrew’s poems bear the date 1686 they were published about the time Damaris wrote this letter.

97 [Mary Astell], Letters Concerning the Love of God (London, 1695); [Damaris Masham], A Discourse Concerning the Love of God (London, 1696); Damaris’s name has been written in by readers in some copies in the Bodleian Library and the British Library, while another has “By John Locke” in ink followed by “No” from another hand. [Mary Astell], The Christian Religion as Profess’d by a Daughter of the Church of England (London, 1705); [Damaris Masham], Occasional Thoughts in Reference to a Vertuous or Christian Life (London, 1705). The 1747 edition of the same text appears as Thoughts on a Christian Life by John Locke, Esq’ (London, 1747). Questions of authorship remained a problem.